ILLIBERAL STATES RULE in the global East and populism provides them with leverage in the global West. Their governing regimes oppose the freedoms of Western democracies, suppress the rule of law, subvert civil society, support anti-democratic movements worldwide, persecute and target critics at home and abroad. The outcome is a foreign and domestic policy in bullish pursuit of authoritarian governance, that is, dark geopolitics.

The lure of dark geopolitics entered the Trumpian force field without difficulty. The gains of democracy after the Cold War were short-lived, rolled back in Russia, Central Europe, and parts of Asia. Trump’s critique of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and his refusal to confront Putin directly have given the Russian president a freer hand from the Baltics to Western Europe. States like Hungary, Poland, and Turkey are showing the world how to progressively dismantle liberal and secular democracies, while keeping their memberships in the EU (Poland and Hungary) and NATO (Turkey).

Trump’s Russia problem would not have arisen and become persistent if Putin’s unfettered personal control over Russia would not embody the paradigm of executive power Trump craves. Putin’s authoritarian liberty is Trump’s leadership model. Make no mistake: Trump and Trumpism would love to bring Putin’s freedoms to the US.

A mural on the outside wall of a barbecue eatery in Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania, depicted Trump’s codependent attraction to Putin rather vividly (Figure 1). As one of the restaurant’s owners noted, Lithuania is “situated on the NATO border with Russia” – an important geopolitical divide between the existence and nonexistence of civil liberties, democratic governance, and peaceful politics.

The Lithuanian mural1 appeared after Trump and Putin began to exchange warm words of admiration in December 2015.2 Their bromance stirred historical memories and collective anxieties in the Baltic region. What were Putin and Trump whispering to each other?

The 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was not forgotten; its secret protocol had paved the way for Stalin’s occupation of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Dominykas Čečkauskas, co-owner of the “small libertarian barbeque joint,” expressed this regional fear: “if Russia and the USA would ever make out, it would happen in the Baltic states … with tongues or with tanks.”3

The possibility of Putin and Trump “making out” is well founded.4 Dark geopolitics is on the rise. Democratic values deemed “Western” are pushed back in more and more countries. Russia and China – the global trendsetters of repressive authoritarian standards – have moved far ahead in restricting political rights, civil liberties, and civil society as well as freedom of expression, press freedom, and freedom of online activities. Yet America, once the cheerleader of the global Freedom Agenda (see chapter 3), is withdrawing from the world under President Trump, pulling back from democracy, political freedom, human rights, and free trade.

Trump’s international withdrawal is weakening the global posture of the US. His pullouts from the Trans-Pacific-Partnership (TPP)5 and the Paris Climate Accord6 are telling Russia and China that the universal principles which Trump’s predecessors championed are history. The America First strategy is isolationist and respects the Sino-Russian spheres of influence. In fact, Trump seems to welcome the advancement of dark geopolitics in the Russian and Chinese world regions.

But an unintended consequence of Trump’s NATO critique could arise: if NATO’s European members would start paying “what they should be paying”7 and became more assertive, the Western military alliance could become stronger and more of an obstacle to the European intrusions of Putin’s Russia.

PROGRESS TOWARD DEMOCRACY came to a global halt in 2006 and began to decline in 2007. This epochal change was observed by Freedom House, a nongovernmental American watchdog organization that has chronicled the worldwide ups and downs of liberal democracy, political freedom, and human rights since 1941.

Freedom House is “dedicated to the expansion of freedom and democracy around the world” and “acts as a catalyst for greater political rights and civil liberties through a combination of analysis, advocacy, and action.”8 This progressive mission of the largely government-funded democracy watchdog and the political values of the current US administration are no longer aligned. And that means shrinking federal support for US democracy assistance is likely.9

Since 1972, the NGO has published its annual flagship report Freedom in the World. In addition, it has released Freedom of the Press since 1980; postcommunist Nations in Transit since 2002; and Freedom on the Net since 2011. Special reports, analytical briefs, and policy briefs on topics related to the NGO’s mission complement its signature reports.

The onset of “freedom stagnation” was diagnosed in Freedom in the World 2007.10 The following year, Freedom in the World 2008 noted, “the year 2007 was marked by a notable setback for global freedom.”11 Since then, each annual Freedom in the World edition has observed a continuing retreat of best democratic practices around the world.

Freedom in the World 2017 has confirmed this unfortunate trend; it counted “a total of 67 countries suffered net declines in political rights and civil liberties in 2016, compared with 36 that registered gains.”12 Besides, it noticed the onset of antidemocratic changes in places that previous reports had rated as “Free.”13

“Partly Free” or “Not Free” countries had gotten worse in the past, but now that formerly stable democracies have come under the influence of populism, their freedoms are in jeopardy as well. Former Soviet Bloc countries, which transitioned from communist regimes to democracies in the 1980s and 1990s, developed xenophobic, counter-democratic, populist agendas in Poland and Hungary. Politicians in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Serbia are encouraged by their neighbors’ trajectory and prepared to turn authoritarian. Trump’s victory has brought the US in line with this trend.

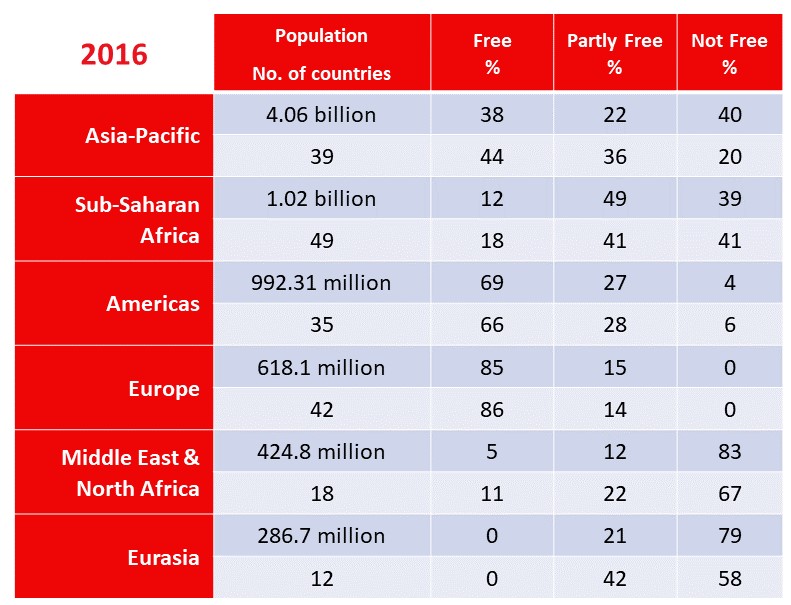

The 2016 global freedom numbers are worrisome. Only 39 percent of the world’s over 7 billion people are considered Free, 25 percent Partly Free, and 36 percent Not Free. For the 195 countries measured, the figures are: 45 percent Free (down from 47% in 2006), 30 percent Partly Free (unchanged), and 25 percent Not Free (up from 23% a decade ago). Table 1 lists the results for all global regions.

Two of the six regions captured in Table 1 stand out from the rest. First, the positive status of Europe because none of its 42 countries is deemed Not Free. And second, the negative status of Eurasia, which includes Russia, because none of its twelve countries is ranked Free. However, the authoritarian trend does not bode well for Europe either. Freedom in the World 2017 underlined, “nearly a quarter of all net declines in 2016” occurred in Europe. And it concluded, “the continent can no longer be taken for granted as a bastion of democratic stability.”

A FREE PRESS is the exception and not the global norm. Only 13 percent of the world population enjoys a Free press. The rest is badly served by a Partly Free press (42%) or worse by a Not Free press (45%). These were the dismal numbers of Freedom of the Press 2017.14 Over two thirds of the 199 countries and territories evaluated did not have a free press.15 More and more journalists around the world are working under political, judicial, and often physical pressure.

For Freedom House, freedom of the media is “a cornerstone of global democracy” and rising authoritarianism is undermining this foundation. Freedom of the Press 2017 pointed out:

Never in the 38 years that Freedom House has been monitoring global press freedom has the United States figured as much in the public debate about the topic as in 2016 and the first months of 2017. Press freedom globally has declined to its lowest levels in 13 years, thanks both to new threats to journalists and media outlets in major democracies, and to further crackdowns on independent media in authoritarian countries like Russia and China.

Freedom House hastened to add, the US “remains one of the most press-friendly countries in the world.” Yet it also warned that Trump’s contempt for “mainstream media” – his utter disregard for facts and hatred of critical reporting, which he calls “fake news” – carries the danger that the US could lose its position as a “model and aspirational standard.”

The cover of Freedom of the Press 2017 shows a pack of wolves named Turkey, Venezuela, Russia, Serbia, Bolivia, Poland, and the Philippines, each ridden by the appropriate strongman (Figure 2). The wolf pack is encircling a bunch of journalists bravely flying a “Free Press” banner. Trump is contemplating the scary scene from the outside.

What is Trump thinking? The report quotes his view of critical journalists as “enemy of the American people” – one of his darkest words. It also highlights his perception of being at war with the press: “I have a running war with the media. They are among the most dishonest human beings on earth.”16 Trump mirrors the mindset of the authoritarian jockeys of the bloodthirsty wolf pack in Figure 2.

AN OPEN INTERNET is not in the interest of illiberal states. This fact was recognized by Freedom on the Net 2016.17 The report measured three kinds of assaults: obstacles to Internet access, limits on content, and violations of user rights; and it documented the decline of Internet freedom “for the sixth consecutive year.”18

The freedom of digital media from government control may become even more important in the future than freedom of the press since an ever-increasing amount of people get their news electronically. In addition, the Internet is still “significantly more free than the news media in general.”19 No wonder, illiberal regimes aggressively pursue and implement restrictions of digital media freedom.

Authoritarian governments employ Internet censorship, user intimidation, and interruptions of Internet services; they block search engines, social media platforms, and communication apps. Their repressive digital control mechanisms undermine and inhibit the activities of liberal democracy and civil society or prevent them from emerging and challenging the tyrannical status quo.

The list of apps that suffered state-sponsored restrictions, disruptions, and periodic or total blocks included Facebook, WhatsApp, Twitter, YouTube, Telegram, and Instagram. Free usage of these apps was also hampered by user arrests.

The “Great Firewall of China,” which regulates and polices the Internet domestically, is a prominent example. Built with oppressive laws and advanced surveillance technologies, it encircles the whole country more seamless than with stones. Around 3,000 major websites are blocked on the Chinese mainland, including all Google services from Gmail to Google Search. A vast army of agents monitors the electronic traffic.

“Deeply concerned” about these “violations and abuses,” the Human Rights Council of the UN affirmed the principle, “the same rights that people have offline must also be protected online.”20 The UN resolution denounced “all human rights violations and abuses committed against persons for exercising their human rights and fundamental freedoms on the Internet” and condemned all “measures to intentionally prevent or disrupt access to or dissemination of information online.” Russia and China tried to “delete calls for states to adopt a ‘human rights based approach’ for providing and expanding access to the Internet.”21

The battle against a free and open Internet is fought overwhelmingly by authoritarian governments, but also democratic states are tempted to control user empowering features. The former have used anti-terrorism laws to punish online activities unrelated to terrorism, such as discussions of democracy and human rights; the latter have demanded “backdoor access” to encrypted communication in the name of the “good fight” against criminals.

Massive despotic repercussions ensued when new social media turned users into authors, publishers, and broadcasters. State authorities took to targeting people who authored, published, or distributed posts, tweets, images, and other content proclaimed illegal or offensive.22 The bevy of forbidden topics covered political opposition, criticism of authorities, corruption, conflict, satire, social commentary, blasphemy, mobilization for public causes, LGBTQ issues, and support of ethnic and religious minorities.

An unfortunate counterpart to the geopolitical repression of Internet freedoms is the flip side of social media user power: the global explosion of trolls and trolling, unfounded, hateful, and untrue postings, unreal news, and bizarre conspiracy theories (see chapter 5).

Yet luckily so far, the Internet still allows many healthy freedoms to bloom. Digital activists keep finding new and creative ways to advocate for democratic change, campaign for women’s rights, combat corruption and waste, publicize official abuses, disseminate suppressed information, save lives in peace and war, organize disaster relief, promote social justice, and foster citizen journalism.

THE GLOBALIZATION OF authoritarian governance is a geopolitical peril the West has not begun to tackle with resolve. Overshadowed by the financial crisis of 2007-2008, then obscured by the smog of populism, and now blocked out by the never-ending eruption of Trumpian conundrums, the US and Western Europe have yet to counterchallenge the deliberate, sophisticated, and increasingly effective repudiation of their democratic identity emanating foremost from Russia and China.

Concerned that “only one side seems to be competing seriously,” fourteen American scholars analyzed the state of “soft-power” competition between autocracies (China, Russia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Venezuela) and liberal democracy in 2016.23 The editors summarized the volume’s wake-up call in The American Interest and underscored the encroaching threat:

The leading authoritarian regimes have invested heavily in building vast and sophisticated soft-power arsenals that now operate in every corner of the world. … At the same time, the most influential authoritarians – China, Russia, and Iran – have become more internationalist. Authoritarianism has gone global.24

Lumping China, Russia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela together as the “big five” is perhaps a bit too generous. Iran and Saudi Arabia are regional but not global powers and constrained by being mortal enemies. Venezuela under the auspices of the “Bolivarian Revolution” led by the late left-wing populist Hugo Chávez and continued by Nicolás Maduro is also neither democratic nor a great power. I would thus discount all three from the five authoritarian countries called “big.”

China and Russia, however, are indeed in the class of great powers, although the former is rising and the latter declining. Both are formidable adversaries, anti-American as well as anti-Western, and eager to seed their specific brands of authoritarianism globally. China prepares for the long run and is presently less menacing than Russia. Moscow pursues its antidemocratic goals more aggressively, as the US found out in its 2016 presidential election.25

THE ILLIBERAL GOVERNMENT of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) invites existing and aspiring authoritarian states to follow its lead and apply the soft and hard power techniques of repressive governance it has developed. China’s lessons include how to create and coopt a large middle class, proactively manage ethnic minorities, suppress political opposition, roll back democratic incursions, and domesticate the Internet.

Knowing that the strategic situation of China is still relatively weak in comparison to the American position and confident that the PRC will eventually surpass the US at least in economic terms, Beijing asserts itself directly only in East and Southeast Asia, the South China Sea for instance, and positions itself otherwise “as a peacefully rising developing country rather than as an assertive great power.”26 But once China’s strategic situation markedly improves, its pragmatic restraint is likely to change.

The accomplishments of the authoritarian Chinese development model are considerable and involve

- holding down political opposition

- concentrating power in one disciplined party

- keeping foreign influences in check

- matching Western technoscientific advancements

- and growing the national economy.

The Chinese model cannot afford the freedoms of liberal democracy and the country’s political elite knows that very well. It has studied the rise and fall of dictatorial regimes far and wide – from the rule of Mexico’s Institutional Revolutionary Party (71 years) to the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (74 years) – and has learned to be always careful and yet decisive.

President Xi Jinping and the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) are pursuing their collective dream of national greatness fully aware of what is at stake.27 They are vigilant adversaries of liberal democratization at home and smart if often heavy-handed exporters of their authoritarian governance program abroad.

China’s growing international outreach portfolio holds many soft-power enterprises: “512 Confucius Institutes and 1073 Confucius Classrooms in 140 countries and regions”28 as well as numerous media outlets including China Daily, China Radio International, Xinhua News Service, and China Global Television Network (CGTN).

The resemblance of these propaganda channels to German Goethe Institutes, Deutsche Welle, BBC World News, and CNN is no accident – they are designed as competitive lookalikes. However, it would be naïve to think that the employees and contractors of the Chinese entities could show, write, or say anything not sanctioned by the strict guidelines and “thought directives” of the CCP.

Confucius Institutes and Chinese media are not expected to indulge in critical programming and editorial independence. They are obliged to put China in a good light and amplify the party line for their main target audiences, overseas Chinese and sympathetic non-Chinese foreigners. They are expected to heed President Xi’s politburo advice from January 2014 on “Constructing a Socialist Cultural Great Power and Improving Cultural Soft Power”:

China should be portrayed as a civilized country featuring a rich history, ethnic unity, and cultural diversity, and as an Eastern power with good government, a developed economy, cultural prosperity, national unity, and beautiful scenery.29

State television is China’s premier propaganda tool. Its brand has evolved from a local orientation (Beijing Television 1958) through a national focus (China Central Television 1978) to its current global emphasis (CGTN 2016).

Channels with an official “Beijing Angle” geared to an increasingly global audience, variously named CCTV International, CCTV-9, and CCTV News (English), started to broadcast and expand since the 1990s when Western inclined outlets, such as Voice of America and BBC World Service, began to retreat with drastic cutbacks of staff and reporting.

CGTN is headquartered in a dazzling skyscraper by international star architects Rem Koolhaas and Ole Scheeren.30 Two years after the cantilevered building’s completion, President Xi asserted his China First approach in a speech against “weird [foreign] architecture.”31 CGTN has regional command centers in Washington, Nairobi, and London; it operates in over 70 countries and broadcasts in Mandarin, Spanish, French, Arabic, Russian, and English.32

China’s global news service is characterized by high production values, slick professionalism, and ubiquitous availability on the Internet (cgtn.com). Its free app can be downloaded from iTunes, Google Play, and Amazon; you are invited to follow it on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and other social media. Censorship is seldom manifest in what is reported – it hides in what is not reported.

An example of China’s modus operandi was given in 2013, when the CCP informed the country’s professors about “Seven Don’t Mentions”: “press freedom, universal values, civil society, civil rights, judicial independence, historical mistakes of the Chinese Communist Party, and the authoritarian-capitalistic class.”33

The latter referred to the wealth accumulated by top Chinese government officials and their families. Of course, what applies to Chinese classrooms, applies to Chinese media as well. Banned and no-go-areas are simply not showing up in CGTN’s news coverage. Hence, they are difficult to spot and the reporting seems to be fine.

POSTCOMMUNIST RUSSIA UNDER Putin is an autocratic state that propagates authoritarianism not with his own model but by fostering turmoil in other societies. Mainly interested in weakening the Western paradigm of liberal democracy and its associated values, Putin offers nothing much in constructive terms, yet gladly assists and supports whatever and whoever promises to sow diversion and upheaval outside the borders of Russia.

Putin’s Russia is not bound by truth, facts, or ideology, it takes sides strategically, left, right, or whatever – anything goes if it diminishes the West. Russia’s international news network, which was founded in December 2005 as Russia Today and rebranded RT in 2009, is an important instrument in this regard. It employs over 1,000 media professionals worldwide and is broadcast by paid partner networks in more than 100 countries.

The network is focused on the US, the Middle East, and Europe, the area of its largest audience, with bureaus in Washington, New York, Baghdad, Cairo, Gaza, London, and Berlin. In 2015, on RT’s tenth anniversary, its channels were reportedly accessed by tens of millions of people daily.34

RT supports digital platforms in English, Arabic, German, French, Spanish, and Russian; it runs a 24-hour English news channel, seven days a week; it is piped into over 2.7 million hotel rooms and provides a free mobile app in the Microsoft, iTunes, and Google Play stores; it also claims to outrank everybody else in terms of news consumption on YouTube.35

RT distributes the critique of “mainstream media” voiced by populist politicians in Europe and the US. Building upon the disruptive groundwork of Tea Party Republicans like Sarah Palin (“lamestream” media) and presidential lies36 about “fake news,” it smartly advertises itself in the Android app store not as an exacerbator (what it is) but a problem solver: “RT news – find out what the mainstream media is keeping silent about.”

The self-description of RT in the Apple app store – “We are set to show you how any story can be another story altogether”37 – leads straight into the twilight zone of Putin’s postmodern world full of “absurd arguments, lies, and half-truths”38 in which “alternative facts” (Conway) “correct” true facts and imaginary news “balance” real news. Instances of this “vast scripted reality show”39 include

- “interviews” with Russian actors playing “victims” of Ukrainian “fascists”

- “exposing” the CIA behind each prodemocracy movement in the world

- and “wondering” if the Ebola outbreak was engineered by the US.

Brandishing the open-minded slogan “Question More”40 and featuring Pamela Anderson and Julian Assange as romantic freedom fighters does not endanger Western democracy. What does do that is Russia’s “‘information-psychological’ warfare” (Pomerantsev) that interweaves such stories with an anti-American and anti-Western narrative, libertarian as well as left- and right-wing positions, revelations of imaginary establishment conspiracies, and countless other distortions served up by RT.

RT works for Putin and his goals. Its objective is not the improvement of global news-reporting and -analysis but propaganda designed as “news,”41 especially the obstruction of European unity and the inflaming of intra-American conflicts.

No question, it is a good thing to challenge the Western information dominance, which Voice of America and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty together with broadcasters like CNN Worldwide and news agencies like Reuters established in the second half of the twentieth century. Counter-interpretations, different viewpoints, and unreported news are welcome journalistic additions. However, RT’s editorial practice of “fair is foul, and foul is fair” turns competitive journalism into propaganda warfare, and that is unwelcome.

Sure, American mainstream media and their reporters make mistakes and commit fraud, but they also report their errors and repel journalistic misconduct just as the scientific community deals with fraudulent science: openly and correctively.42

Putin, on the other hand, operates beyond any such code of conduct. And Trump likewise. He pokes fun at CNN as the “Clinton News Network,”43 habitually denunciates critical media, and spreads the lie that the elite US media are “dishonest” and manufacture their news from made-up sources. Trump is thus a most valuable player for Putin, a purveyor of the darkest confusion and corruption that Russia could ever wish upon America.

The Washington Post recently added “Democracy Dies in Darkness” to its masthead.44 Although the paper’s search for a slogan began even before Trump became the Republican nominee, the Post’s new tagline is eerily apt for what has already happened since Trump and Trumpism acquired the White House. Democracy dies and authoritarianism grows in darkness, in dark geopolitics as well as in the dark environs of the Trumpian force field.

- The mural of the Lithuanian graphic designer, Mindaugas Bonanu, paid homage to a famous Cold War photo showing the Soviet leader, Leonid Brezhnev, and his East German ally, Erich Honecker, celebrating the thirtieth anniversary of the German Democratic Republic in 1979 with a “socialist fraternal embrace.” See “The Socialist Fraternal Kiss between Leonid Brezhnev and Erich Honecker, 1979.” Rare Historical Photos, 25 March 2014. One decade later, after the Berlin Wall had fallen, a Russian artist reimagined this photo in a painting on the eastern side of the wall captioned, “Lord help me to survive this deadly love.” This mural by Dimitrij Vrubel is now on permanent street display in Berlin. See “East Side Gallery,” Google Arts & Culture.

- See Damian Kolodiy, “Looking at a Trump-Putin Relationship Timeline.” Huffpost, 15 Feb. 2017.

- Adam Taylor, “The Putin-Trump kiss being shared around the world.” Washington Post, 13 May 2016.

- See Karen DeYoung and David Filipov, “Trump and Putin: A relationship where mutual admiration is headed toward reality.” Washington Post, 30 Dec. 2016.

- Trump started his presidency with a geopolitical gift for China, his withdrawal from the TPP with 11 Pacific Rim nations; see Toluse Olorunnipa, Shannon Pettypiece, and Matthew Townsend, “Trump Revamps U.S. Trade Focus by Pulling Out of Pacific Deal.” Bloomberg, 23 Jan. 2017.

- Another turning-backwards point was reached in June 2017 when Trump announced his decision to withdraw from the Paris Climate Accord signed by 195 nations; see Michael D. Shear, “Trump Will Withdraw U.S. From Paris Climate Agreement.” The New York Times, 1 June 2017.

- Philip Rucker, Karen DeYoung, and Michael Birnbaum, “Trump chastises fellow NATO members, demands they meet payment obligations.” Washington Post, 25 May 2017.

- “About Us.” Freedom House. Accessed 1 June 2017. Update Dec. 2020: The current wording of “About Us” has changed but not its anti-authoritarian, pro-democracy spirit.

- The Trump Administration has proposed a 30% cut in democracy support in its budget request for the Fiscal Year 2018; see “United States: Administration’s Budget Request Undermines U.S. Global Leadership.” Freedom House, 22 May 2017. Update Dec. 2020: The FY18 Trump cuts of democracy programs have continued for FY19; see “United States: Cuts to Democracy Funds Reduce U.S. Security.” Freedom House, 11 Feb. 2018.

- See Freedom in the World 2007. Rowman & Littlefield, New York and Washington 2007.

- Freedom in the World 2008.

- Arch Puddington and Tyler Roylance, “Populists and Autocrats: The Dual Threat to Global Democracy.” Freedom in the World 2017, p. 1.

- The ranking system of Freedom House differentiates between Free, Partly Free, and Not Free; see “Freedom in the World 2017: Methodology,” p. 3: “The average of a country’s or territory’s political rights and civil liberties ratings is called the Freedom Rating, and it is this figure that determines the status of Free (1.0 to 2.5), Partly Free (3.0 to 5.0), or Not Free (5.5 to 7.0).”

- See Freedom of the Press 2017, Freedom House, April 2017.

- The details of this worsening trend are as follows: 33 percent of all surveyed countries had print media that were Not Free (up from 32%), 36 percent had a Partly Free press (up from 30%), and only 31 percent got their news from a Free press (down from 38% in 2006). The Not Free group involved 66 countries. The worst top ten countries were: North Korea and Turkmenistan (both scored 98 – score 100 is Least Free), Uzbekistan (95), Crimea and Eritrea (both 94), Cuba and Equatorial Guinea (both 91), Azerbaijan, Iran, and Syria (all 90). As of December 2016, Turkey stood out in the Not Free category for having thrown a record of 81 journalists into jail.

- Michael J. Abramowitz, “Press Freedom in the United States: Hobbling a Champion of Global Press Freedom.” Freedom of the Press 2017. Freedom House, April 2017, p. 2. For the original context of this Trump quote, see Julie Hirschfeld Davis and Matthew Rosenberg, “With False Claims, Trump Attacks Media on Turnout and Intelligence Rift.” The New York Times, 21 Jan. 2017.

- See Sanja Kelly, Mai Truong, Adrian Shahbaz, and Madeline Earp, “Silencing the Messenger: Communication Apps under Pressure.” Freedom on the Net 2016, Freedom House, November 2016.

- Freedom on the Net 2016 assessed 65 countries and 88 percent of the world’s Internet population of some 3.2 billion people from Most Free (0 points) to Least Free (100 points). The countries designated as Free (0-30 points), Partly Free (31-60 points), and Not Free (61-100 points) ranged from Estonia and Iceland (both 6 points) to China with 88 points. 17 countries scored Free, 28 Partly Free, and 20 Not Free. The freedom of contemporary netizens improved only in 14 countries. The largest declines in the last five years were engineered in the Ukraine (27 to 38 points), Venezuela (46 to 60 points), Turkey (48 to 61 points), Russia (52 to 65 points), and Ethiopia (75 to 83 points).

- See above, note 17, p. 26. For further analysis, see Alexander Klimburg, The Darkening Web: The War for Cyberspace. New York: Penguin Press, 2017.

- UN Human Rights Council, “The promotion, protection and enjoyment of human rights on the Internet.” United Nations, 27 June 2016.

- “UNHRC: Significant resolution reaffirming human rights online adopted.” Article 19, 1 July 2016.

- For example, a Russian engineer was given a two-year prison sentence because he had shared material that affirmed the Crimean Peninsula as part of the Ukraine. It did not matter that he informed only twelve of his contacts. Turkey punished posters and re-posters juxtaposing public images of Erdogan with film shots of the Gollum character from Lord of the Rings. Saudi Arabia sentenced a man to death for “apostasy” and arrested people for “spreading atheism” online. China imprisoned people “for watching religious videos on their mobile phones.”

- See Larry Jay Diamond, Marc F. Plattner, and Christopher Walker, eds., Authoritarianism Goes Global: The Challenge to Democracy. A Journal of Democracy Book. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016. The book has two parts, “The Authoritarian ‘Big Five’” (I) and “Arenas of ‘Soft-Power’ Competition” (II). All fourteen chapters had appeared throughout 2015 in the Journal of Democracy, a publication of the bipartisan National Endowment for Democracy.

- Christopher Walker, Marc Plattner, and Larry Diamond, “Authoritarianism Goes Global: Undemocratic states are kicking their influence-peddling machines into high gear.” The American Interest, 28 March 2016.

- See US Intelligence Community, “Background to ‘Assessing Russian Activities and Intentions in Recent US Elections’: The Analytic Process and Cyber Incident Attribution.” Office of the Director of National Intelligence, 6 Jan. 2017.

- Andrew J. Nathan, “China’s Challenge,” in Diamond, Plattner, and Walker, eds., Authoritarianism Goes Global, op. cit., p. 35.

- See, for example, “Xinhua Insight: Xi leads nation in pursuing Chinese dream in new year.” Xinhuanet, 6 Feb. 2017. For the country’s increasingly powerful leader, the “Chinese Dream” is a vision of national greatness and historical redemption. The most hawkish formulation to date has been delivered by a retired Chinese colonel; see Liu Mingfu, The China Dream: Great Power Thinking & Strategic Posture in the Post-American Era. New York, NY: CN Times Books, 2015.

- As of December 2016; see Jeffrey Gil, “China’s Confucius Institute: working to plan?” Asian Studies Association of Australia, 12 June 2017.

- Quoted from Anne-Marie Brady, “China’s Foreign Propaganda Machine,” in Diamond, Plattner, and Walker, eds., Authoritarianism Goes Global, op. cit., p. 192.

- See “CCTV Headquarters.” The Skyscraper Center.

- Amy Frearson, “‘No more weird architecture’ says Chinese president.” Dezeen, 20 October 2014.

- See “ABOUT US – China Global Television Network.”

- Anne Nelson, “CCTV’s International Expansion: China’s Grand Strategy for Media?” Center for International Media Assistance, 22 Oct. 2013, p. 22.

- See “RT watched by 70mn viewers weekly, half of them daily – Ipsos survey.” RT, 10 March 2016.

- See “Most Watched News Network on YouTube” with “over four billion views” as of January 2017. Accessed 20 June 2017. Update Dec. 2020: This claim has risen to “OVER 10 BILLION VIEWS” in January 2020. User numbers of RT are hard to verify and probably inflated.

- Tradition would find it inappropriate to call a sitting president a liar but Trump has forfeited that respect; see David Leonhardt and Stuart A. Thompson, “Trump’s Lies.” The New York Times, 23 June 2017, updated 14 Dec. 2017.

- “RT News.” Apple App Store.

- Lilia Shevtsova, “Forward to the Past in Russia,” in Diamond, Plattner, and Walker, eds., Authoritarianism Goes Global, op. cit., pp. 40-56.

- Peter Pomerantsev, “The Kremlin’s Information War,” in Diamond, Plattner, and Walker, eds., Authoritarianism Goes Global, op. cit., pp. 174-186.

- Steven Erlanger, “Russia’s RT Network: Is It More BBC or K.G.B.?” The New York Times, 8 March 2017.

- For example, after the downing of Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 on 17 July 2014 RT initially insinuated, “President Putin’s plane might have been the target for Ukrainian missile-sources.” See John Plunkett, “Russia Today reporter resigns in protest at MH17 coverage.” The Guardian, 18 July 2014.

- See, for instance, how the Times handled the dishonesty of one of its own reporters: “Times Reporter Who Resigned Leaves Long Trail of Deception.” The New York Times, 11 May 2003.

- Tim Hains, “Trump: Fake News Media Making Up Anonymous WH Sources; CNN Is ‘Clinton News Network’.” Real Clear Politics, 24 Feb. 2017.

- See Paul Farhi, “The Washington Post’s new slogan turns out to be an old saying.” Washington Post, 24 Feb. 2017.