TRUTHS TO ONE side of the political spectrum, lies to the other – how is that parallax possible? Well, good stories don’t lie; the hero always wins; and Trump is the hero in a galaxy of narrative truths.1 If you live in a world with factual truth, your sun shines in another universe.

Consider the following: On July 24, 2017, the National Jamboree of the Boy Scouts of America featured a “hyper- political speech” by President Trump that was meant to be apolitical.2 On July 25, Trump claimed, “I got a call from the head of the Boy Scouts saying it was the greatest speech that was ever made to them, and they were very thankful.”3 On July 27, the Chief Scout Executive apologized to the scouting family about the “political rhetoric that was inserted into the jamboree.”4 And on August 1, the scouting organization told Time they were “unaware of any call from national leadership placed to the White House.”5

On August 2, a reporter, who was following up on the emerging story, asked White House press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders, “Why did the president say that he received a phone call from the leader of the Boy Scouts and the president of Mexico when he did not? Did he lie?”6 When Sanders acknowledged that no phone calls had been received, the reporter concluded, “So he lied.” But when Sanders heard that, she said no, “It wasn’t a lie. That’s a pretty bold accusation.” Hence, the question arises: What has happened to the distinctions between beliefs, opinions, lies, facts, and truth?

We understand Trump is a businessman who has learned that selling an apartment, a building, or himself works better with hyperbole than unvarnished truth in advertising. Trumpian reality is built on opinions, wishful thinking, and make-belief. What remains unclear is: Why do so many people buy the Trumpian hocus pocus with facts and truth?

Reality in Trump world is a matter of perspective. Take the “Trump Tower” on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. The tower has 68 floors in Trump’s marketing information. Creative floor accounting has logged the soaring atrium as 10 floors, added the 19 commercial floors above it, and brought the subsequent first residential floor to number 30.7 Counting the concrete floors would have arrived at number 20 (and 58 for the whole building).

When “Trump World Tower,” a residential condominium opposite the UN in New York, had to indicate floors on the elevator panels, Trump “counted” 90 stories, although the building had only 72 constructed floors to walk on. How did he do it? Trump divided the 900-foot-tall building by an average floor height of 10 feet. An average height of 9 feet would have given him 100 floors. “I could have gone higher than 90 stories,” Trump was quoted in the New York Times, but “I chose 90 because I thought it was a good number.”8

Trump has been credited, and proudly credits himself, with the invention of vanity marketing floors that replace the tedium of actual floors. Trumpian math is popular in the luxury real estate business and appeals especially to men of new wealth for whom an apartment’s size and altitude are tokens of accomplishment. The higher up, the better, and if the number on the elevator button shows the owner’s lofty status, why not?

Trump has grasped the social psychology and motivating power of aspirational illusions early on. The Art of the Deal made no bones about it:

The final key to the way I promote is bravado. I play to people’s fantasies. People may not always think big themselves, but they can still get very excited by those who do. That’s why a little hyperbole never hurts. People want to believe that something is the biggest and the greatest and the most spectacular. I call it truthful hyperbole.9

Still, “selling fantasy” for a healthy profit with gimmicks like higher numbered floors is not always sufficient. Aggressive strategies for beating the competition are also required. Trump’s salesmanship has no problem with that:

I’m the first to admit that I am very competitive and that I’ll do nearly anything within legal bounds to win. Sometimes, part of making a deal is denigrating your competition.10

Trump’s business acumen did not fall by the wayside when he transitioned into the presidency. His formation as a wheeler-dealer carried over with all its canny and uncanny elements. Trumpian mythmaking produced a grandfather who allegedly came to America “from Sweden”11 and intimations about President Obama’s supposedly non-American birthplace.12

Trump operates in the amusing realm of extravagant exaggerations and the demagogic jungle of wildly untruthful claims. He has inflated his height by one inch13 and did not hesitate to declare the size of his hands cum private parts as “normal” and “slightly large, actually.”14 Yet he also linked Rafael Cruz, the father of his rival Ted Cruz, to the assassination of John F. Kennedy15 and argued that Obama “was the founder of ISIS.”

Trump aims his dark words deliberately. When conservative radio talk show host Hugh Hewitt in an otherwise compliant interview suggested that “founder of ISIS” might be a mistake, Trump said, “No, it’s no mistake. Everyone’s liking it.”16 And when Hewitt offered, “I’d just use different language” to convey the ISIS claim, Trump shot back, “But they wouldn’t talk about your language, and they do talk about my language, right?” Hewitt responded, “Well, good point. Good point.”

Trump is never at odds with himself. What is wrong with calling Obama the founder of ISIS when “everyone’s liking it”? And what could be better than everybody is talking about “my language”? Non-Trumpers may be hung-up on terminology and facts, but Trump supporters “get” Trump the way he understands himself. They follow the narrative truth of his words.

Trump and his people dwell in a postmodern world where the distinction between “factual” and “narrative truth” is suspended. Ben Shapiro, a former editor-at-large of Breitbart, expressed this observation in a remark about Breitbart and Bannon:

I knew Andrew [Breitbart] since I was 16 and the idea that he and Bannon were best friends and that Bannon was the natural heir was utter bullshit. Truth and veracity weren’t [Bannon’s] top priority at Breitbart. Narrative truth was his priority rather than factual truth.17

Shapiro has called Bannon and Trump “mirror images of each other.” Both have made their home in a world where reality-based politics has become an “elite thing.” Unmoored from facts and truth, Trump and Trumpism emanate from, and resonate in, the space of thought that postmodern philosophy has opened wide in the last forty years.

DARK PHILOSOPHY LETS the truths of all narratives bloom. An arcane study of the role of narrative in the social construction of individual and collective identities has taken to the streets and turned into the everyday application of postmodern relativity. Now, the doctrine of equal rights for all storytelling rules. The corrosive consequences of this thought change are ubiquitous.

Pure falsehoods have been elevated to “alternative facts.”18 Cynical slogans, such as “Fair & Balanced”19 for Fox News, cover hyperpartisan rants. Prejudice-reinforcing conspiracy theories can be widely distributed without shame and penalties. Political propaganda outlets are encouraged to practice RT’s black magic of “how any story can be another story.”

What began as a critique of the infinite-progress hype surrounding Western civilization has become an uncritical, generalized thought position. To comprehend this transformation, we must understand a French philosopher, Jean-François Lyotard, and his seminal work The Postmodern Condition.20

Lyotard qualified the European Enlightenment as a metanarrative in which “the hero of knowledge works toward a good ethico-political end – universal peace.”21 For Lyotard, a “metanarrative” is a second-order story about the “little narratives” (petits récits) people tell each other. And from these popular stories and tales – plural histories, so to speak – a singular story is fashioned for a community, a nation, or a culture. Yet that unified (hi)story violates the authenticity, diversity, particularity, and incompatibility of the original micronarratives of the people. Ergo, metanarratives (also called “grand narratives” by Lyotard) are essentially false narratives.

To put it differently, the grand narrative of the Enlightenment culminating in universal peace was but a big lie – a “mythistory”22 that suppressed the oppression of non-conforming ideas and people on behalf of the imagined march of history towards a fully enlightened society. Lyotard deemed the critique of such fables the objective of postmodern philosophy and wrote, “I define postmodern as incredulity toward metanarratives.”

In the late 1970s, when Lyotard formulated his philosophy of the postmodern condition, he noted that the Enlightenment narrative was losing “its great hero, its great dangers, its great voyages, its great goal.” He interpreted this change as “a product of progress in the sciences.”

As “postmodern knowledge” advanced, the statues of Christopher Columbus, Vasco da Gama, Ferdinand Magellan, and Hernán Cortés began to melt. Traditional textbook chapters about the heroic age of discovery became obsolete. One-sided celebrations of Columbus Day were protested, and local histories of pre-Columbian Native Americans featured. The complex interplay between rapacious European colonizers and indigenous populations emerged. And all that happened because “our [postmodern] sensitivity to differences” and “ability to tolerate the incommensurable” grew and gained strong intellectual traction.

Postmodern critical theory of the Enlightenment developed in opposition to Critical Theory with capital letters. Lyotard rejected the Frankfurt School approach of Jürgen Habermas who had defended the Enlightenment as an “unfinished project.”23 The French philosopher endorsed the relativity of norms and ideas and asked, “Is legitimacy to be found in consensus obtained through discussion, as Jürgen Habermas thinks?” Lyotard did not think so (“Such consensus does violence to the heterogeneity of language games”).

Lyotard promoted “inventor’s paralogy” (new things, rules, and ideas via “dissension”) in contradistinction to Habermasian discourse theory. He criticized the legitimation of power structures by metanarratives (such as the march of modern science towards rational explanation of everything or the global advancement of universal human rights) and featured the articulation of different beliefs, desires, and aspirations “in clouds of narrative language.”

However, two historical developments problematized the postmodern critique itself. First, people did not heed the philosopher’s prescription to banish grand narratives, in fact, they created new ones, the metanarrative of globalization, for example. Globalists hailed the “flattening” of the world with unrestricted communication, open borders, and free trade.24 But populists and authoritarian strongmen rallied their troops against unfettered globalization, and the likes of Decius-Anton, Bannon, and Estulin are now nurturing anti-globalism as a grand counter-narrative.

Second, far from eliminating metanarratives, postmodernism has only succeeded in liberating all narratives from the restrictions of factual accuracy, scientific objectivity, social fairness, moral rectitude, and personal honesty. When postmodernism trickled down from its original philosophical heights to Rorty’s “postmodernist professors” (see Foreword above), their students, and ultimately the Trumpian base, it toppled all naïveté about facts and truth, indeed it sidelined the quests for facts and truth and mainstreamed the stories people tell on Facebook, Twitter, and other social media.

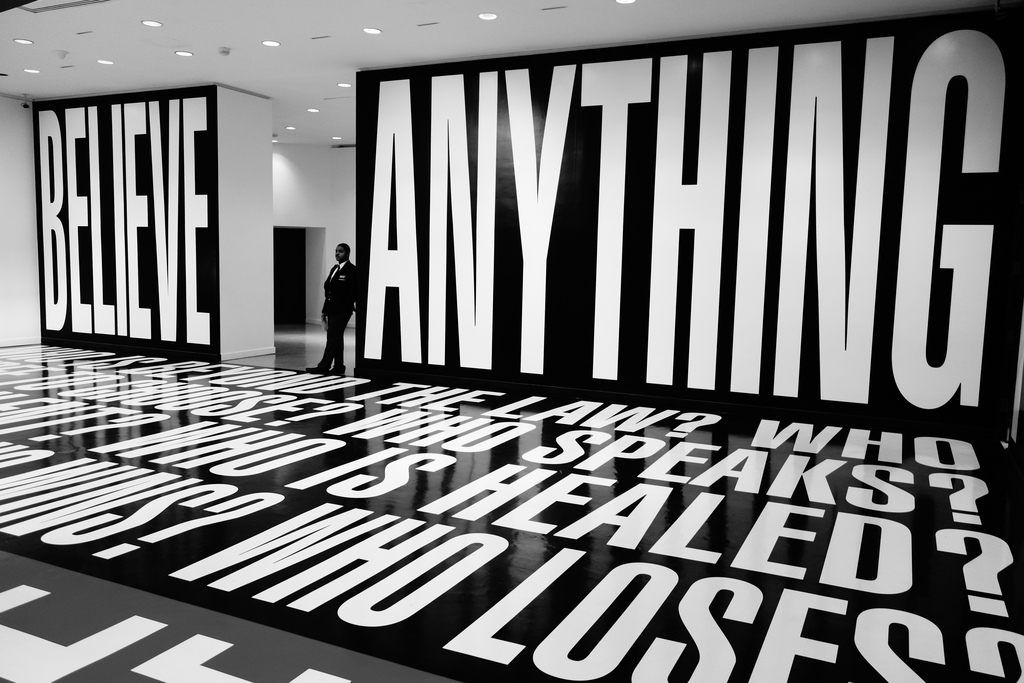

The postmodern review of presumptuous Enlightenment claims thrived in the 1980s and 1990s. It was an overdue and warranted intervention, but the corrective critique became a problem when paralogy changed from remedy to prescription (Figure 1), that is, when postmodernism began to spread narrative truths wholesale and empowered the epistemological anarchism of “anything goes.”25

POSTMODERN RELATIVITY IS the result of surging narrative truths and ebbing factual truth. It is transmitted in, and by, the small particles of language, the words we speak, read, and write. Every ideological sea change occurs in language first and must spark novel words subsequently. Postmodernism affirmed that rule with “post-truth” – a word first used in 1992.

Oxford Dictionaries named “post-truth” the international Word of the Year 2016.26 It defined the adjective as “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than emotional appeals.” It also revealed that “its usage increased by 2,000% in 2016 compared with last year.” Casper Grathwohl, President of Oxford Dictionaries, described the word’s career:

Fuelled by the rise of social media as a news source and a growing distrust of facts offered up by the establishment, post-truth as a concept has been finding its linguistic footing for some time. We first saw the frequency really spike this year in June with buzz over the Brexit vote and again in July when Donald Trump secured the Republican presidential nomination. Given that usage of the term hasn’t shown any signs of slowing down, I wouldn’t be surprised if post-truth becomes one of the defining words of our time.27

The Society for German Language elected “postfaktisch” (the German loanword for post-truth) also Word of the Year 2016 (followed by “Brexit” in the number two position).28 A noteworthy feature of both the English and German neologisms appears when one realizes that postfaktisch is not counterfactual (kontrafaktisch in German) but something else entirely. The Economist highlighted that by calling post-truth politics a new mindset in Austria, Germany, North Korea, Poland, Russia, Turkey, the UK, and the US in which “truth is not falsified, or contested, but of secondary importance.”29

Post-truth and post-truth politics have entered the English language and Wikipedia for good. The linguistic innovation was foreshadowed by “truthiness,” a word Stephen Colbert had launched in The Colbert Report in 2005. The comedian’s mock term took off when the American Dialect Society called it the 2005 Word of the Year and explained, “truthiness refers to the quality of preferring concepts or facts one wishes to be true, rather than concepts or facts known to be true.”30

Now that truth is no longer the shared priority of speech for politicians, the media, and the public, but merely an optional feature of communication, the problem arises: Whose post-truth dominates the ferociously competitive 24-hour news cycle?

In 2002, a senior adviser to President George W. Bush answered that question in a meeting about an article that had irritated the Bush White House. The aide told the writer, Ron Suskind, journalists like him were living “in what we call the reality-based community” – bad company in the eyes of the aide and the White House. The aid’s further clarification that Suskind and his kind “believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality” puzzled Suskind. Yet when Suskind interjected something about “enlightenment principles and empiricism,” the aide (believed to be Karl Rove) cut him off and declared:

That’s not the way the world really works anymore. We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you’re studying that reality – judiciously, as you will – we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors . . . and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.31

True, power politics has always produced “new realities” for writers to report and historians to study. But political actors and observers also always had a shared sense of “discernible reality” – until the rise of narrative truth.

The evolution from Bush’s “faith-based presidency” (Suskind) to the dreamed-up worlds of conspiracy and fiction (Trump world) is devastating. America has slit down the slippery slope from boldly creating its own imperial reality and tipped over into the realms of fantasy. Old-fashioned politics as “a strong and slow boring of hard boards” (Max Weber) has fallen into oblivion. The holders of state power and millions of anonymous “history actors” are now producing invented-reality stories on social media every day.

Great private wealth has shifted from the landowners of long ago (George Washington) over yesterday’s real estate tycoons (Fred and Donald Trump) to the social media entrepreneurs of today (foremost Mark Zuckerberg). The inclination of social media toward mass plantings of irrealities combined with the proclivity of superior wealth to inspire delusions of expertise32 is extremely worrisome for the present and the future.

Trump admitted in Art of the Deal that “modest” is not his favorite word, yet Trump’s analog boasting pales in comparison to the digital capabilities of a Zuckerbergian government33 that would operate on a post-truth basis:

We believe in giving people a voice, which means erring on the side of letting people share what they want whenever possible. We need to be careful not to discourage sharing of opinions or to mistakenly restrict accurate content. We do not want to be arbiters of truth ourselves, but instead rely on our community and trusted third parties.34

The formula for an updated brave new world is clear: Start with the libertarian “Mercer” constant (a person’s net worth is a person’s value), add both the Trumpian equation (superrich equals most knowledgeable) and the value of avowed agnosticism about truth, then multiply the result with algorithmic social media superpower. The terrible outcome is no longer unimaginable.

The empowerment of the voices of all people and the postmodern relativity of all truths have created myriads of Zuckerbergian “dumb fucks.”35 Are we looking into a global future of billionaire dictators presiding over rival narratives? Is there a way out of this predicament? Can we return from post-truth to factual truth? Can we reign-in populism and authoritarianism? Yes We Can. Make Trumpism Small Again!

- See Ashley Lamb-Sinclair, “When Narrative Matters More Than Fact.” The Atlantic, 9 January 2017.

- Chris Cillizza, “The 29 most cringe-worthy lines from Donald Trump’s hyper-political speech to the Boy Scouts.” CNN, 27 July 2017.

- Josh Dawsey and Hadas Gold, “Full transcript: Trump’s Wall Street Journal interview.” POLITICO, 1 Aug. 2017.

- Michael Surbaugh, “From the Chief: Our Perspective on the Presidential Visit.” Scouting Wire, 27 July 2017.

- Alana Abramson, “Boy Scouts ‘Unaware’ of Call Trump Said He Received from Organization Praising Jamboree Speech.” Time, 1 Aug. 2017.

- Jonathan Easley, “White House: Trump did not lie about phone call from Boy Scouts.” TheHill, 2 Aug. 2017. On July 31, after the swearing-in of John Kelly as new chief of staff, Trump also claimed to have received a congratulatory call from Mexico’s president for the decrease in illegal border crossings. But the Mexican President’s Office quickly declared: “President Enrique Peña Nieto has not been in recent communication via telephone with President Donald Trump.” See Kevin Liptak, “Trump’s call history called into question.” CNN, 2 Aug. 2017.

- See Vivian Yee, “Donald Trump’s Math Takes His Towers to Greater Heights.” The New York Times, 1 Nov. 2016.

- Ralph Gardner Jr., “For Tower Residents, a New Math.” The New York Times, 8 May 2003.

- Donald J. Trump and Tony Schwartz. Trump: The Art of the Deal. New York: Ballantine Books, 2015, p. 58. First published by Random House in 1987.

- Ibid., p. 108.

- Trump’s grandfather immigrated to the US from Kallstadt in Germany; see Jason Horowitz, “For Donald Trump’s Family, an Immigrant’s Tale With 2 Beginnings.” The New York Times, 21 Aug. 2016.

- See Gregory Krieg, “14 of Trump’s most outrageous ‘birther’ claims – half from after 2011.” CNN, 16 Sept. 2016, and Josh Voorhees, “All of Donald Trump’s Birther Tweets.” Slate, 16 Sept. 2016.

- See Darren Samuelsohn, “Trump’s driver’s license casts doubt on height claims.” POLITICO, 23 Dec. 2016.

- Philip Rucker and Robert Costa, “Donald Trump: ‘My hands are normal hands’.” Washington Post, 21 March 2016.

- See Robert Farley, “Trump Defends Oswald Claim.” FactCheck.Org, 22 July 2016.

- Duane Patterson, “Donald Trump Makes a Return Visit.” The Hugh Hewitt Show, 11 Aug. 2016.

- Matthew Garrahan, “Breitbart News: from populist fringe to the White House and beyond.” Financial Times, 7 Dec. 2016.

- Aaron Blake, “Kellyanne Conway says Donald Trump’s team has ‘alternative facts.’ Which pretty much says it all.” Washington Post, 22 Jan. 2017.

- “Fair & Balanced” was the Fox News motto since 1996. It was replaced in 2017 by “Most Watched, Most Trusted.” See Michael M. Grynbaum, “Fox News Drops ‘Fair and Balanced’ Motto.” The New York Times, 14 June 2017.

- Jean-François Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Translated by Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984. First French edition 1979: La Condition Postmoderne: Rapport Sur Le Savoir. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit. The English translation is available online.

- For this and all following quotes, see Lyotard, op. cit. 1984, pp. xxiii-xxv.

- The term was embraced by American world historian William McNeill in Mythistory and Other Essays. Chicago and London 1986. I have criticized the legitimization of mythistory; see Wolf Schäfer, “Global History: Historiographical Feasibility and Environmental Reality,” in Global History, ed. by Bruce Mazlish & Ralph Buultjens, San Francisco and Oxford 1993, pp. 47-69. An excerpt of my critique is available here.

- See Jürgen Habermas, Die Moderne – Ein Unvollendetes Projekt (Theodor-W.-Adorno-Preis 1980). Frankfurt am Main: Amt für Wissenschaft und Kunst, 1981. English translation in: Maurizio Passerin d’Entrèves and Seyla Benhabib, Habermas and the Unfinished Project of Modernity: Critical Essays on The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity. Studies in Contemporary German Social Thought. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1997. Also available online.

- See Thomas L. Friedman, The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005.

- Paul Feyerabend, Against Method: Outline of an anarchistic theory of knowledge. London 1975, p. 28: “there is only one principle that can be defended under all circumstances and in all stages of human development. It is the principle: anything goes.” Feyerabend and Lyotard were well aware of, and sympathetic to, each other’s work.

- See Alison Flood, “‘Post-Truth’ named word of the year by Oxford Dictionaries.” The Guardian, 15 Nov. 2016.

- “‘Post-truth’ declared word of the year by Oxford Dictionaries.” BBC News, 16 Nov. 2016.

- See “GfdS wählt ‘postfaktisch‘ zum Wort des Jahres 2016.” Gesellschaft für deutsche Sprache, 9 Dec. 2016.

- “Post-truth politics: Art of the lie.” The Economist, 10 Sept. 2016.

- “Truthiness Voted 2005 Word of the Year.” American Dialect Society, 6 Jan. 2006, and Ben Zimmer, “Truthiness.” The New York Times, 13 Oct. 2010.

- Ron Suskind, “Faith, Certainty and the Presidency of George W. Bush.” The New York Times, 17 Oct. 2004.

- See Aaron Blake, “19 things Donald Trump knows better than anyone else, according to Donald Trump.” Washington Post, 4 Oct. 2016.

- See Keith A. Spencer, “Mr. Zuckerberg, please don’t run for president: The last thing America needs is a Facebook technocrat.” Salon, 8 July 2017.

- Mark Zuckerberg, “Post.” Facebook, 19 Nov. 2016.

- Nicholas Carlson, “Well, These New Zuckerberg IMs Won’t Help Facebook’s Privacy Problems.” Business Insider, 13 May 2010. After launching the original Facebook website in his Harvard dorm room in 2004, the young Zuckerberg told a friend that he had over 4,000 emails, pictures, addresses etc. from “anyone at Harvard.” Asked by the friend, “How’d you manage that one?” Zuckerberg answered, “People just submitted it. I don’t know why. They ‘trust me.’ Dumb fucks.”