POPULISM IS A wish-machine running on the words believe me. Usually, that “me” is a strongman, yet it can also be a strong woman these days.1 European dictators have activated this machine since classical times, from Caesar to Napoleon, Mussolini, Stalin, and Hitler. It is employed globally in our time. Nicolás Maduro, Recep Erdoğan, Rodrigo Duterte, and the Kim dynasty are pitching their versions of it in Venezuela, Turkey, the Philippines, and North Korea.

Historically, populism has defaulted to authoritarian rulership – Caesarism, Bonapartism, Fascism, Stalinism, National Socialism, or some other creed. The historical record also proves that populist regimes tend to pile up horrendous costs for the people and countries that fall for their promises. Why should the US under Trumpism be an exception? Eventually, all Americans will have to pay for the follies of the Trumpian wish-machine.

Trump makes promises without regard for their costs or how to fulfill them. He often says “believe me,” though hardly ever “I believe.”2 He constantly vows to “Make America Great Again” (MAGA, a trademarked slogan), is always right and successful, and never fails to achieve something. The Washington Post listed 76 promises Trump made from the start of his campaign in June 2015 to January 2016. Here is a small sample from this list. Trump vowed to

- call for a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States”

- build a wall at the southern border of the US and make Mexico pay for it

- never take a vacation while serving as president

- bring jobs back from China, Mexico, Japan, and elsewhere

- deport almost 11 million undocumented immigrants living in the US

- and start winning again.3

Why “winning again”? America and its people must have been beaten and let down – but by whom? Regular politicians, of course. “Politician” is a curse word in the dictionary of populism. Trump’s base perceives him as far removed from this despised kind. He is the redeemer that has descended from the height of his worldly achievements to elevate the country and its people. The MAGA wish-machine promises “win after win after win,” which is to say, fight after fight after fight. On April 11, 2016, at a rally in Albany, New York, Trump shouted:

We’re going to win so much – win after win after win – that you’re going to be begging me: ‘Please, Mr. President, let us lose once or twice. We can’t stand it anymore.’ And I’m going to say: ‘No way. We’re going to keep winning. We’re never going to lose. We’re never, ever going to lose.4

The fantasy that all fights will be won and no fight lost is matched by the illusion that nobody will have to pay for these fights. American soldiers and taxpayers will lose neither blood nor treasure. Supporters of populist movements do not care about intellectual consistency. If someone convinces them, as Trump did, that he is the one who will “totally” beat everybody and everything that stands between their encumbered lives and wishful dreams, their enthusiastic support will carry that person to the helm. The blues and reckoning come later.

POPULISM IS A promiscuous affair covering the political spectrum all the way from Right to Left. Traditional fidelities like patriotism and religion have no intrinsic value. They are just resources for seducing the masses. Facts and truth are irrelevant. Trump can say that he attends a specific church in Manhattan, even if that church denies that.5

Populists are contradictory, slippery, and elusive. Yet herein lies their deceiving strength. Without any commitment to a particular program, philosophy, or theory of history (as in Marxian communism), the populist leader is boundlessly flexible and able to pitch his rhetoric to what the people want to hear. He will automatically say the right thing because he “gets” the people.

All populisms have also two things in common: Timely methods of direct communication and a spectrum of anti-attitudes. Populist communicators have always sought the most direct mode of addressing their base, from public oratory in the Roman Forum to Hitler’s radio speeches6 and today’s YouTube videos and Twitter messages. Throughout history, populist speakers have reached audiences with plain language and dog-whistles7 in the early stages of their careers.

The anti-attitudes of populism account for the rousing content and fire of populist speechmaking. There is no stable set of resentments, only a wide array of options of “enemies of the people.” The selection is driven by the understanding of who stands in the way of the people and their leader. It can be immigrants, democrats, liberals, Muslims, journalists, newspapers, experts, professors, foreign students, socialism, capitalism, the elite, the media, the European Union, big business, big banks, Wall Street, multinationals, drug dealers, corruption, globalization, whoever and whatever. The anti-attitude may target a singular culprit (“the Jew” in Nazi Germany) or focus on any combination of criminalized offenders.

The preference of populist movements for direct communication between leader and audience creates a structural barrier against intermediaries. Typically, “the establishment,” political and professional elites, independent institutions, and critical media are met with hostility. Nationalism and nativism are habitually allied with right-wing populism, which is mostly inward-looking. Left-wing populism has sometimes favored international instead of national solidarity (“Workers of the World Unite!”), but that was before the global age. Now, cosmopolitanism is suspicious to all populists.

When populist nationalism merges with an anti-attitude such as antisemitism, the stadium chant “USA! USA!” becomes “Jew-S-A! Jew-S-A!” This noxious transformation was displayed in October 2016 by George Lindell, a Trump supporter wearing a “Hillary for Prison” T-shirt at a rally of his candidate.8 Yelling at the corralled press corps, “You’re the enemy, you’re the ones working for the devil,” Lindell’s outburst unleashed the dark energy of an individual. However, the “us” versus “them” worldview is also a collective property of populism with deadly potential for internal and external foes. Collective eruptions of dark energy from populist movements (pogroms) are to be expected and feared.

The explosive dynamic of the “friend-enemy antithesis” has received notorious attention and support by political theorist Carl Schmitt (1888-1985). This foremost Weimar and Nazi jurist emphasized the “objective nature” of the friend/enemy binary in “the political.”9 For Schmitt, the political conceives the enemy as “the other, the stranger.” Explaining the otherness of the other, Schmitt stated: “it is sufficient for his nature that he is, in a specially intense way, existentially something different and alien, so that in the extreme case conflicts with him are possible.” Schmitt underlined that such conflicts can include violent action in “war between organized nations” or “civil war.” Why? Because “to the enemy concept belongs the ever-present possibility of combat.” Finally, Schmitt stated that the terms “friend” and “enemy” have to be understood in their “original existential sense” as words with corporal relevance, “because they refer to the real possibility of physical killing.”

Considering this conclusion and the extensive historical record of populist adventures in conjunction with the novel prospects of America under a populist president, it would appear prudent to look at history with Schmitt’s chilling analysis in mind. But no, half of America’s political elite is too excited about their new career chances, whereas the other half is too stunned about their lost opportunities. Meanwhile, the frightening possibilities down the road begin to take roots.

The United States of America has a dangerous sense of incomparability. It prides itself as being exceptional and forward-looking, so it doesn’t bother to spend time studying the past. Why learn from the experience of other nations when your country is unique? Why clutter your mind with old stuff when the future will bring new things? America skips the history lessons. She dismisses the devastating victories of populism as a European or Latin-American problem. Only in fiction, as in The Plot Against America by Philip Roth (2004), has the US fallen to a president inspired by Nazi Germany, or taken over by a populist strongman, as in Sinclair Lewis’s novel It Can’t Happen Here (1935).10

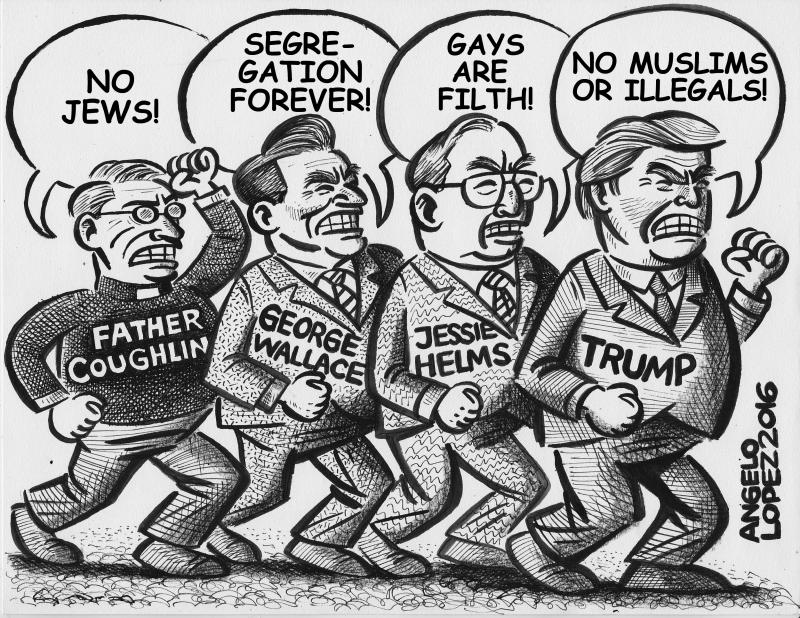

The centrist elites of America hesitate to acknowledge that the upstart populist leader, who has already acquired the White House, could dismantle American democracy, or that the country’s longstanding political culture, stability, and order could slowly be ripped to shreds. American democracy and its institutions are perceived as healthy and robust.11 They have survived McCarthyism and Governor Huey Long’s authoritarian inclinations; they weathered the antisemitism of Charles Coughlin, the racism of Governor George Wallace, and the LGBTQ hatred of Senator Jesse Helms (Figure 1). Indeed, America has seen demagoguery, violence, hate-crimes, darkly scheming fringe groups, and all sorts of killings, but she has never been possessed by an admirer of strongmen and a militant populist movement.

Trump was carried to the pinnacle of American power by a multitude of evitable ills, including

- angry frustration of Whites without a college degree

- dispirited and pained Blacks who abstained from voting

- widespread distrust of Hillary Clinton

- Democratic Party neglect of the working-class

- identity politics for the well-educated

- successful Russian intelligence efforts

- and a toxic sludge of falsehoods widely publicized by the myriad tentacles of social media.

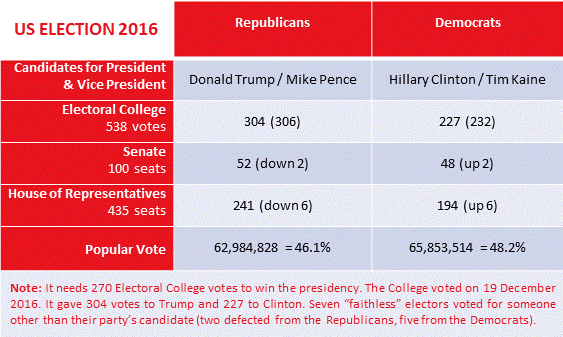

Thus, on November 8, 2016, Trump received the votes that gave him a clear majority in the Electoral College (Table 1). He became President of the United States on January 20, 2017. Since then, Trump and Trumpism are in power. Dark words and dark forces must now be reckoned with. They are inflating the Trumpian universe and will affect everybody everywhere for the rest of this decade and probably beyond.

POPULISM HAS INFECTED the US deeply and conquered its highest office. What appeared to be a distant issue has now entered the mainstream of American politics.

The American international studies establishment took belated notice. Case in point: The Foreign Affairs issue on “The Power of Populism.” Published just before the 2016 election, it was led off by a “fascinating” interview with Marine Le Pen, the female leader of France’s right-wing National Front. The journal’s contributors echoed the editorial line, “politics as usual is unlikely to return anytime soon,”12 but sounded only moderate warnings.

Sheri Berman declared “Populism Is Not Fascism, But It Could Be a Harbinger.”13 Breaking old ground, Michael Kazin distinguished two American populist traditions, one advancing “civic” and the other “racial nationalism.”14 Erroneously assuming that the latter would be “no longer acceptable in national campaigns,” Kazin found, “Trump will struggle to win the White House.” He concluded, “populism can be dangerous, but it may also be necessary” to invigorate American democracy.

Observing that “the populist fever” is rising “almost entirely in the Western world,” Fareed Zakaria diagnosed “too rapid cultural change” caused by transnational migration.15 He prescribed “limits on the rate of immigration and on the kinds of immigrants who are permitted to enter,” but remained confident that the West will manage, since “young people are the least anxious or fearful of foreigners of any group in society.” The emerging prominence of populism in Western societies was also the topic of Cas Mudde’s article “Europe’s Populist Surge.”16 Having researched European populism for two decades and knowing its wide range and deep historical roots,17 Mudde rightly emphasized the “likely staying power”18 of parties built around populist appeals.

In contrast to the presidential system of the US, where the leader of the executive is elected more directly,19 the parliamentary systems of Europe elect their executive leaders (the Prime Minister of the UK or the Chancellor of Germany, for instance) more indirectly, that is, via the legislators of the parties represented in the national parliament. Moreover, gaining more than one-third of the national vote has become almost impossible in the multi-party systems of Europe. Hence, European parties need to forge governing coalitions and can rarely seize power abruptly. A quick winner-takes-all surprise like Trump’s is unlikely in contemporary Europe.

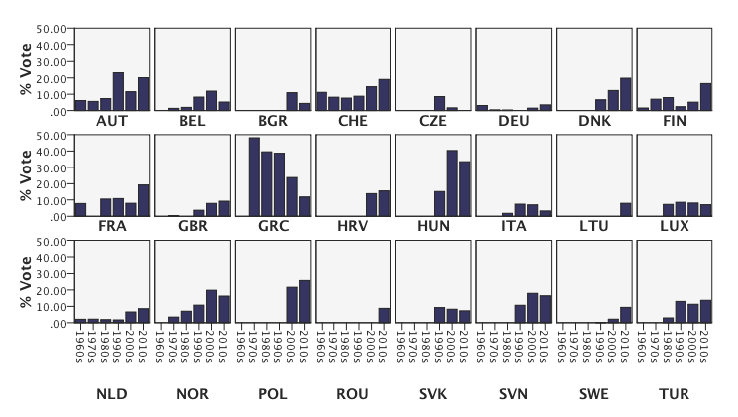

Right- and left-wing populist parties are already in the parliaments of most European countries gathering votes and power over successive election cycles. They articulate the populist zeitgeist and hold quite a few seats.

Collectively, populist parties scored an average of 16.5 percent of the vote in those elections [in the five years before 2016 in 16 European countries], ranging from a staggering 65 percent in Hungary to less than one percent in Luxembourg. Populists now control the largest share of parliamentary seats in six countries: Greece, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Slovakia, and Switzerland.20

So far, European populism is moving largely within established, lawful political frameworks. Nevertheless, democracy and freedom in Europe are not guaranteed. According to Mudde, Europe’s growing populism is “essentially illiberal, especially in its disregard for minority rights, pluralism, and the rule of law.” Viktor Orbán, Prime Minister of Hungary and leader of its populist Fidesz party, confirmed this proudly when he said, “the new state that we are building in Hungary is an illiberal state, not a liberal state.”21 In addition, antidemocratic Far Right alliances and populists managed to get EU funds for their anti-EU agendas. Leading representatives of Eurosceptic parties (such as the UK Independence Party) won seats in the European Parliament, which gave them salaries, benefits, titles, media exposure, and immunity from criminal prosecution in their home countries.22 UKIP’s Nigel Farage – Brexit advocate, friend of Trump, and Fox News commentator – is a prime example of a cynic EU populist responsible for Europe’s creeping advancement of corrosive populism.

Until recently, Germany was the European country with the lowest voting support for populist parties (Figure 2). Its gaggle of small populist movements included the Alternative for Germany (Alternative für Deutschland, AfD).23 Founded in February 2013, the AfD did not win enough votes in September 2013 to enter the national parliament, yet by May 2017, it had representatives in thirteen of Germany’s sixteen state parliaments. Looking forward to an announced (but then unrealized) opening of Breitbart bureaus in Cairo, Paris, and Berlin, the Heidelberg AfD branch tweeted in ecstatic anticipation: “Breitbart is coming to Germany. Fantastic! That’ll cause an earthquake in our stale media landscape.”24

The national emergence of the AfD occurred in the federal elections of September 24, 2017, when this new right-wing force gained 12.6 percent of all votes and became the third-largest party with 94 seats in the German parliament (the Bundestag). Although Angela Merkel won a fourth term as chancellor, her party (CDU) shrunk by 55 seats, and her previous coalition partners (SPD and CSU) lost 40 and 10 seats, respectively.25 The AfD has succeeded in spiking German politics with inflammatory, neo-nationalistic and anti-immigration rhetoric and topics, but still has little chance of entering a national governing coalition.

To fathom the populist breakthrough in the US, I will deep-dive into the abyss of Trumpism next.

- The gender gap in the leadership of populist movements is narrowing. Men dominated in the past, but women are catching up. The Peronist Cristina Fernández de Kirchner followed her husband, Néstor Kirchner, as president of Argentina. Marine le Pen assumed the leadership of the French Front National (FN) from her father, Jean-Marie Le Pen. The German Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) is currently (2017) headed by Frauke Petry, and so are two Scandinavian right-wing populist parties, the Dansk Folkeparti (DF) and the Norwegian Fremskrittpartiet (FrP). See Susi Meret & Birte Siim, “Female Charismatic Leaders for ‘Männerparteien’?”

- Matt Viser, “Donald Trump relies on a simple phrase: ‘Believe Me’.” BostonGlobe, 24 May 2016, and Tyler Schnoebelen, “Trump says ‘believe me’ often but rarely ‘I believe.’” Medium, 21 Oct. 2016.

- Jenna Johnson, “Here are 76 of Donald Trump’s many campaign promises.” The Washington Post, 22 Jan. 2016.

- Jon Campbell “Donald Trump ‘wins’ in 50 seconds” (with video).

- Eugene Scott, “Church says Donald Trump is not an ‘active member’.” CNN, 28 August 2015. Also, Trump does not understand the differences among Christian denominations, they are all evangelicals to him; see Antonia Blumberg, “Donald Trump Apparently Doesn’t Know Which Christians Are Evangelicals.” Huffington Post, 2 June 2017.

- The telling German word for the iconic radio that transmitted the speeches of Hitler was Volksempfänger, People’s Receiver (Volk means people). On a 1936 poster, it was promoted with the words “All of Germany hears the Führer with the People’s Receiver.” The inexpensive radio was developed at the request of Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels. It went on sale in the fall of 1933 as model VE301. “VE” stood for Volksempfänger and “301” for the day Hitler became Chancellor, 30 January 1933.

- Ian Haney López, 27 Sept. 2016, “Campaign 2016 Vocabulary Lesson: ‘Strategic Racism’.”

- Daniel Politi, “Watch Trump Supporter Chant ‘Jew S.A.’ at Reporters, Call Them ‘Enemy’ at Rally.” Slate, 30 Oct. 2016. For more on this, see Stephen Lemons, “Trump Supporter George Lindell, the ‘Jew S.A.’ Guy, Explains His Views on Race, Religion, and Slaves.” Phoenix New Times, 2 Nov. 2016.

- Carl Schmitt, The Concept of the Political. Translated by George Schwab. With “Notes on Schmitt’s Essay,” a translation of Leo Strauss’s “Anmerkungen zu Carl Schmitt, Der Begriff des Politischen” (1932); an Introduction by George Schwab; and a Foreword by Tracy B. Strong. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007, p. 27. The first German version was published as a journal article in 1927; a revised book version came out in 1932.

- When asked what he thinks about Trump, Roth said: “he makes any and everything possible, including, of course, the nuclear catastrophe.” See Judith Thurman, “Philip Roth e-mails on Trump.” The New Yorker, 30 Jan. 2017.

- After the election of Trump, two Harvard professors of government, Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt, having “spent two decades studying the emergence and breakdown of democracy in Europe and Latin America,” prominently asked in The New York Times, “Is Donald Trump a Threat to Democracy?” (18 Dec. 2016). Drawing on a “litmus test” checking the acceptance of violence, the desire to jail rivals, and the willingness to deny the outcome of elections, they correctly concluded: “Mr. Trump tests positive. In the campaign, he encouraged violence among supporters; pledged to prosecute Hillary Clinton; threatened legal action against unfriendly media; and suggested that he might not accept the election results.” Yet Levitsky and Ziblatt ended reassuringly, “American democracy is not in imminent danger of collapse. If ordinary circumstances prevail, our institutions will most likely muddle through a Trump presidency.” However, they also wondered how American democracy under Trump would fare in a crisis caused by war, terrorist attack, or riots and protests.

- Gideon Rose, Editorial: “The Power of Populism,” Foreign Affairs, vol. 95, 2016, no. 6.

- Foreign Affairs, vol. 95, 2016, no. 6, p. 39. Berman defines right-wing populism as “a symptom of democracy in trouble” and fascism as a “consequence of democracy in crisis” (p. 44).

- Foreign Affairs, “Trump and American Populism. Old Whine, New Bottles,” vol. 95, 2016, no. 6, p. 17.

- Foreign Affairs, “Populism on the March. Why the West Is in Trouble,” vol. 95, 2016, no. 6, pp. 14, 11, and 15.

- Cas Mudde, “Europe’s Populist Surge: A Long Time in the Making,” Foreign Affairs, vol. 95, 2016, no. 6, p. 25-30. For a selective overview, see “Europe’s Rising Far Right: A Guide to the Most Prominent Parties,” The New York Times, 4 Dec. 2016.

- [Cas Mudde, Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007. For a newer analysis of the expansive European populist scenery, see Ruth Wodak, The Politics of Fear: What Right-Wing Populist Discourses Mean. London: Sage, 2015.

- Cas Mudde, “Europe’s Populist Surge,” Foreign Affairs, vol. 95, 2016, no. 6, p. 25.

- Since the American president is finally chosen by the Electoral College, a body constituted for the sole purpose of electing the president, the US discussion centers periodically on abolishing the Electoral College and opening the path to the presidency via popular vote instead. It has happened five times in US history that a candidate won the presidency without winning the popular vote. The Democrats have experienced this setback twice in the twenty-first century. It could become a pattern if the Electoral College persists.

- Mudde, op. cit., p. 26.

- See “Proclamation of the Illiberal Hungarian State.” Speech at the annual Transylvanian “Tusványos” Summer University and Student Camp in Romania, 26 July 2014.

- See “MEPs Condemn €600,000 EU Grant for Far-Right Bloc.” BBC News, 5 May 2016, and James Kanter, “Far-Right Leaders Loathe the European Parliament, but Love Its Paychecks.” The New York Times, 27 April 2017.

- The German populist scene featured Liberal Conservative Reformers (Liberal-Konservative Reformer, LKR) and Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamization of the West (Patriotische Europäer gegen die Islamisierung des Abendlandes, PEGIDA). Concerning the AfD, see Amanda Taub and Max Fisher, “Germany’s Extreme Right Challenges Guilt Over Nazi Past,” The New York Times, 18 Jan. 2017.

- Jörg Luyken, “Could Breitbart Influence Next Year’s German Election?” The Local, 16 Nov. 2016.

- Bundestagswahl 2017. See also Steven Erlanger, “Germany’s Far Right Complicates Life for Merkel, and the E.U.” The New York Times, 25 Sept. 2017, and Melissa Eddy, “Alternative for Germany: Who Are They, and What Do They Want?” The New York Times, 25 Sept. 2017.