TRY TO ANSWER the question: Is technology per se good, evil, or neutral, and you will quickly get into epistemological trouble. To avoid this trap, I enter this discussion at the usage station, the point from whence technologies are part and parcel of modern societies, embedded in social, natural, cultural, and economic activities, open to political interests, and subject to ethical distinctions between good and bad uses.

The Flight 93 airplane lent itself to the pilot and the terrorists; both were flying the aircraft within our planet’s atmosphere and our moral and political universe. Hence, when I speak of dark technology, I mean technology used for bad ends and not technology as such. Social media are no exception: digital messaging technologies, like airplanes, lend themselves to good and bad uses, and everything in-between.

Technology darkens when rogue users of Facebook, Twitter, and other social media concoct fake news, or when Donald Trump and radical Trumpists inject dark words and sinister memes into the echo chambers of social networks.1 It is an unacceptable breach of public trust when shiny new techtools are used to attack and destroy what we hold dear: democracy, civil society, civility, tolerance, fair play, public courage, ecological balance, and truth. But make no mistake, getting dark words and fake news into mass circulation are highly valued achievements on the shady side of technology, and not only for the agents of Putin’s democracy-disrupting media and intelligence operation, but also for America’s bad political actors on behalf of T-Plus.

The brave new world of social media is still in its teenage years. Nothing is settled, change is constant, everything evolves at blinding speed. Young billionaire owners and millionaire managers of social media platforms have mind-bending influence over large swaths of Earth’s people. Sophisticated software engineers are in over their heads in terms of ethics, politics, privacy, and other societal concerns. Digital literacy is scarce among end users. Everybody is involved; nobody is truly in charge; all are vehemently unprepared.

Our seemingly simple messaging tools have quickly become an irresistible force with myriad local and global repercussions and rapidly spreading use and abuse. Technology-driven societies are wedded to these adolescent tools. Let’s proceed with caution and not presume full understanding and knowledge.

Facebook and Twitter are prime examples for the immaturity of the new social media. Each service was tested and explored for about a year before facebook.com and twitter.com became available: Facebook in August 2005 and Twitter in April 2007. Twitter was not even ten years old when Trump was elected. Facebook hit humanity when humanity’s experience with traditional books was 550 years old (counting from the printing of the Gutenberg Bible in 1455 to 2005). We have lived with printed books for over half a millennium, whereas the exposure to our novel information and communication systems has been a dozen years.

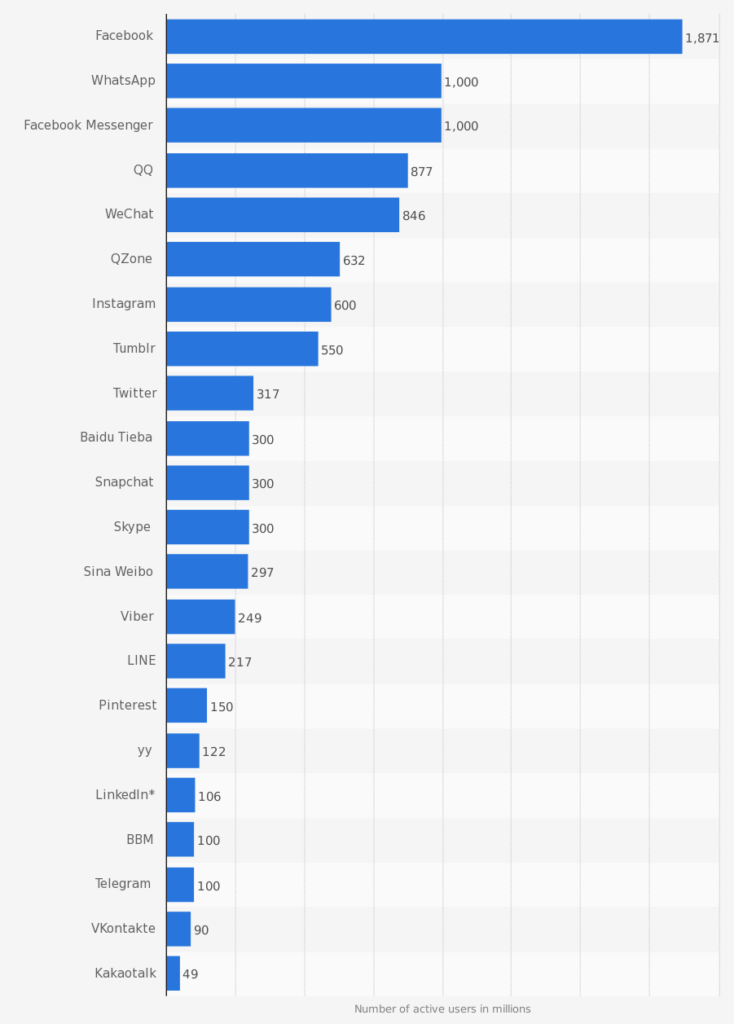

In 2010, a Google engineer estimated how many original books had been published with moveable type technology during the “Gutenberg Galaxy.”2 Nearly 130 million was his number.3 This is a small figure in comparison to the amount of participants in social media today. In January 2017, monthly active social media users (who incidentally are also “authors,” “publishers,” and “re-publishers”) were over 1,800 million for Facebook and 317 million for Twitter (Figure 1). 130 million printed books over five-and-a-half centuries versus 1.8 billion social network accounts created in the comparative blink of an eye is a spectacular difference.

In June 2017, Facebook counted 2 billion monthly users.4 The social media platform reached that number in less than twelve years; Twitter climbed to its relatively modest 317 million in less than ten. Of course, this is a bit of an apples-and-oranges comparison since we don’t know the grand total of all readers of printed books stored in public and private libraries. However, active accounts of monthly users garnered by social media in just twelve years have probably already surpassed the number of all the people who read a book since the Italian Renaissance.

The electronic human is not growing up fast enough. It has superseded Marshall McLuhan’s “typographic man,” but the “ehuman” is still evolving. It barely knows itself or how to calibrate its digital power tools for the best of society. Information retrieval and news consumption have gone from printed books and newspapers to Facebook, from seventeenth century pamphlets to microblogs, and from eighteenth century coffeehouses to Twitter – all in a fraction of a single lifetime and with little understanding of the whole. The number of players in human affairs has exploded and the place of action has shifted onto screens.

Humanity’s time to adapt to this momentous change has been ultrashort. Advancements in computing have quickly passed through major hard- and software transitions: from workstations to desktops, laptops, tablets, and ever more capable smartphones as well as from passive consumption of static websites (Web 1.0 at least since 19945) to interactive and user-generated content (Web 2.0 since about 2004). Ehumans must keep up with their constantly developing tools; they must absorb the innovations as they arrive and cannot stop to reflect.

TRUMP’S UNEXPECTED ELECTION spurred the recognition that consequential global and local technology changes have occurred and are afoot. Top publishers of news, such as the New York Times, were forced to admit – as much to themselves as to their readers – that they had not kept pace with these changes, more importantly, that social media had “subsumed and gutted” traditional media:

The election of Donald J. Trump is perhaps the starkest illustration yet that across the planet, social networks are helping to fundamentally rewire human society. They have subsumed and gutted mainstream media. They have undone traditional political advantages like fund-raising and access to advertising. And they are destabilizing and replacing old-line institutions and established ways of doing things, including political parties, transnational organizations and longstanding, unspoken social prohibitions against blatant expressions of racism and xenophobia.6

Only after the 2016 election did the old media recognize their blinders. Then, in the aftermath, they looked back in shock and realized: “The pro-Trump media understood that it was an insurgent force in a conversation conducted on social media on an unprecedented scale.”7

Traditional media failed to discover and discuss the rising pro-Trump insurgency before the election. However, reporting this news now – belatedly – is bringing mainstream journalism up to date. The Gutenberg bias, which favored printed news and dismissed what was happening in the ocean of electronic conversations, is on its way out.

The rapidly increasing numbers of users of social media signal a historical break away from print media and into the unlimited virtual territories of the digital realm with its big waves, deep currents, and huge storms. Social media platforms, such as Facebook and Twitter, benefitted from this sea change. Facebook’s real-world dominance is even more breathtaking if one considers that the next two platforms with over one billion active users each – WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger – also belong to Mark Zuckerberg’s Facebook, Inc.

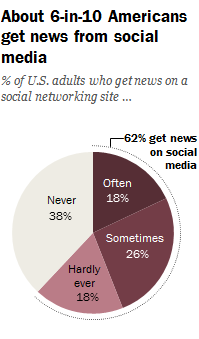

In 2017, two-thirds of all Facebook users followed news on Facebook, and, according to a Pew Research social media update for 2016, 79 percent of US adults logged into Facebook in early 2016.8 Hence, news circulating on Facebook could reach over half of the American adult population (two thirds of 79, i.e. some 52 percent). And social media news exposure is trending upward.

In 2012, 49 percent of US adults got their news from social media. The number went up to 62 percent in early 2016 (Figure 2). Does that foreshadow the rise of fake news? We don’t know yet. Serious research about the electoral impact of fake news has only begun.9

Social media feed their news and information to ever more people. In addition, videos from Google owned YouTube teach crocheting, tell what is happening in Yemen, and demonstrate fidget spinner tricks. Opening the heavy tome of a multi-volume encyclopedia or the large broadsheets of a printed newspaper has become so yesterday. Will that make upsets à la Trump the new normal? Conceivably, but only in the absence of widespread electronic news literacy. Have false news stories swayed the 2016 election? Maybe, maybe not. But the dark possibility alone invites the abuse of social media for nefarious political objectives.

User time spent on social platforms is also growing. In January 2017, Nielsen reported 7 hours per week for Generation X (ages 35 to 49) and 6 hours for Millennials (ages 18-34), up from the third quarter of 2015 by 29 and 21 percent, respectively. Drawn in by the excitement of the election, social media time for US adults over 50 increased by 64 percent in the report’s period. Simultaneous use of multiple devices (TVs, laptops, handhelds) is regular now; smartphones have become ubiquitous (96 percent for adults 18 to 34); and wireless mobile web access is rising fast. Facebook was the top social media application on US smartphones with 178.2 million unique users in September 2016.10 One could say, America runs on Facebook.

IN MAY 2016, Gizmodo, a design, technology, science, and science fiction website, caused a stir reporting, Facebook “routinely suppressed conservative news.”11 The New York Times picked the alarm up and weighed in, “Conservatives Accuse Facebook of Political Bias.”12 The accusation of left-wing prejudice at Facebook was news because it contradicted what was known, namely the instrumentalization of Facebook and Twitter by the Right for both the American election and the European Brexit campaign.13

The political bias accusation led Facebook to fire its flesh and blood news curators in August 2016 and change its “Trending” news feature to “a more algorithmically driven process,” that is, machine automation. Now, the company could announce that its news section “will no longer require people [my emphasis] to write descriptions for trending topics.”14

Facebook was considering bias as a uniquely human feature, thinking it could put the insinuation of being a liberal leaning social media platform to rest by invoking the objectivity of scientific computation. However, the firm’s assumption that bias does not apply to “neutral” code was a mistake. Algorithms are not neutral. They calculate measurable factors correctly but optimize selected parameters for a valued result. The desired output is chosen by Facebook and its programmers who are writing code “to maximize your engagement with the site and keep it ad-friendly.”15

Facebook’s clever switch to un-curated, machine-selected news backfired when the world learned that several Facebook posts that went viral – for example, “Denzel Washington backs Trump in the most epic way” or even better, “the Pope has endorsed Donald Trump” – were planted fakes. The belated recognition of the dark political impact of social networks must be noted again. The social media problem of fake news had manifested itself before the election yet was tackled by the mainstream media only after the election. Then it was reported as a major problem of Google and Facebook and not as a serious traditional news reporting oversight as well.16

However, biased computing remains a problem for Google, Facebook, Twitter and others. Google has promoted fake news through its ads business. As far as corrective measures go, Google tried to finetune its advertising policies and recalibrate its search algorithms. In 2017, the company disclosed the amount of blocked “bad ads”: 1.7 billion misleading ads in 2016 (double the amount of 2015). Google made it also known that a large team (reportedly “thousands”) is monitoring the technology that was designed to automatically spot bad ads and publishers.17

Monitoring the algorithmic automatons of social media is the industry’s quandary. Consequently, Facebook is still tinkering with the “trending topics” section. In January 2017, it changed its newsfeed algorithm once more, which now has descriptive headlines again and aggregates publishers of the same story (instead of how many people are talking about a story) to “help ensure that trending topics reflect real world events being covered by multiple news outlets.”18 Facebook also hired a former TV anchor to “foster transparent dialogue with news organizations globally.”19

Technology firms like Google and Facebook have a genuine problem with journalism when it comes to the selection of news. A motto like “All the News That’s Fit to Print” (on the front page of the New York Times since 1896) raises their suspicion. They wonder, who decides about the criteria for fitness to print or post? An editorial voice is the last thing they want to have or get. Even though their business model promotes eyeballs, clicks, likes, shares, and comments for increased profits, which is not a neutral goal, they want to stay close to their technological roots and apply “neutral” methods to pick the news. A business insider, Antonio Garcia-Martinez, who had worked at Facebook and Twitter, called this the mindset of an “engineering-first culture”:

Facebook and Google and everyone else have been hiding behind mathematics. They’re allergic to becoming a media company. They don’t want to deal with it. An engineering-first culture is completely antithetical to a media company.20

To resolve the “neutral” algorithm issue, social media companies need to transcend their proud STEM attitude, which puts science, technology, engineering, and mathematics above society. Perfect algorithmic computing is not averse to bias. As Zeynep Tufekci noted regarding Facebook’s newsfeed algorithm, “it’s perfectly plausible for Facebook’s work force to be liberal, and yet for the site to be a powerful conduit for conservative ideas as well as conspiracy theories and hoaxes.”21 Facebook’s “real bias” is built into its algorithms. Social media algorithms function in, and are written for, a corporate environment with powerful, technology-defining interests.

TRUMP WAS SET to become a world leader on Twitter.22 He created his Twitter account early, in March 2009. From the start of his campaign, Trump was savvy about the online networking tool, understood its populist power and wide-open reach.

On November 7, the day before the election, Trump had some 13 million “followers” (the Twitter equivalent of “friends” on Facebook). His Twitter ranking at that point was 127 out of 317 million global Twitter accounts. Two days after the election, his ranking had jumped 20 points to number 107 with over 14 million followers worldwide. Trump broke into the top 100 ranks on November 12, 2016, and occupied rank 31 on July 9, 2017, with over 33.5 million (real and fake) followers.23 On his way up in the “Twitterverse,” Trump surpassed Google, BBC World News, the Economist, the National Football League, and NASA. To his chagrin, he still trailed CNN, the New York Times, and Barack Obama by mid-2017.24

Trump has employed social networking tools, primarily Twitter, for dark ends with unmatched demagogic skill. Although his tweets may seem to have caught up to him at times, they always kept his brand name in the news.25 More importantly, his nonstop anti-immigration, anti-Muslim, anti-refugee, anti-Clinton, anti-establishment, and anti-mainstream-media messages kept his supporters glued to his tweets and delivered voters.

From May 2009 to January 2017, Trump posted over 30,000 tweets. His daily average increased from less than 1 in 2009/10 to over 20 in 2013. During his candidacy in 2015/16, the daily average was slightly over 15.

Politico Magazine compiled a graphical analysis of Trump’s tweeting history from May 2009 to April 2016, which highlights his favorite words (“I”), terms (“Winner”), and adjectives (“Sad!”); the top countries in “Donald’s World”: China, Iran, Iraq, and ISIS (in that order); and the top issues for users of Twitter who mentioned Trump: immigration (46%), foreign affairs (29%), taxes (12%), and health care (7%).26 Since Trump was paying consummate attention to the concerns of his followers, he quickly learned that immigration, more precisely, anti-immigration, was by far the most resonant issue to exploit as candidate and president.

Trump became the number one subject of US Twitter discussions in 2015 with 43 million mentions, followed by Hillary Clinton with 31.5 million. In December 2015, Trump created the third biggest conversational Twitter spike ever with five million conversations about Muslim immigration (the Islamic State terrorist attacks in Paris a month earlier had caused global spike number one). Trump’s heavy and unconstrained tweeting triggered also fake tweets pretending to originate from @realDonaldTrump.27

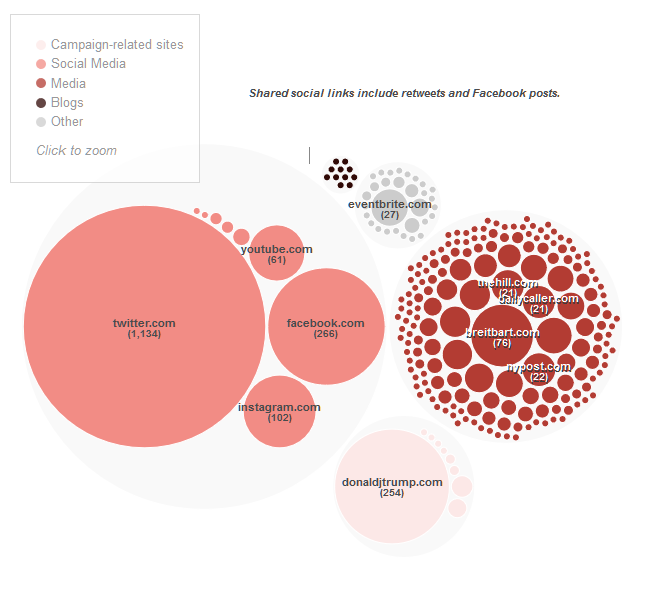

BuzzFeed wanted to know where Trump got his news from, including the stories he broadcasted in tweets and retweets. For this, they sampled the messages that had emanated from Trump’s personal account during his presidential campaign. By extracting 2,687 hyperlinks from the data set and mapping the interesting media landscape they contained, BuzzFeed was able to obtain “a rudimentary portrait of the news and opinion he [Trump] publicizes and, presumably, consumes” (Figure 3).28

Like most Americans, Trump got his news predominantly from social media, mainly Twitter, followed by Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube. Right-wing Breitbart was the news organization he shared the most. Trump’s information ecosystem included mainstream media as well, such as the Washington Post, provided they published positive news about him or polls in his favor. Nevertheless, he preferred content from “right-leaning, hyper-partisan sites and opinion blogs” with an “affinity for factually murky stories bolstered by opinion, circumstantial evidence, and hearsay that appear[ed] generally supportive of his most controversial statements.”

BuzzFeed’s conclusion: candidate Trump favored “sensationalism over facts,” echo chamber tactics (“quotes from … himself or his closest advisers”), critical assessments of his enemies, and uncritical accounts of his own opinions.

Trump was the politician who profited most from dark social media activities in 2016. First, they enabled Trump to communicate directly with his supporters. Second, they allowed him to grow his base below the radar of traditional media, which dismissed him and his base as a vulgar circus until it was too late. Third, they unleashed the pent-up energy of his followers whom he encouraged to employ deceits, such as fake news about celebrity endorsements of their candidate. Fourth, they afforded him and the obscure ideologues of radical Trumpism to develop a game-changing discourse underground. Fifth, they liberated JAG intellectuals and Breitbart provocateurs to go far beyond political correctness and re-introduce banned issues like identity politics for white Americans.

Three takeaways from this chapter: Social media have delivered the perfect tools for a populist in our time. Trump and Trumpism have weaponized a technology that should be liberating. The Trumpian force field has unleashed the dark force of social media.

- For example, Trump’s antisemitic tweet from July 2, 2016: it showed Hillary Clinton’s face in front of a pile of money next to a Star of David inscribed with the words “Most Corrupt Candidate Ever!” Immediately, social media erupted with criticism and within hours the star was covered with a red circle; see Donald Trump, “Crooked Hillary – Makes History!” and Ginger Adams Otis, “Trump posts, quickly deletes image of Star of David next to Hillary Clinton’s face.” NY Daily News, 2 July 2016. What remains disturbing is a) the racist origin of the image, b) that it found its way to Trump, and c) that it became the source of Trump’s tweet; see Anthony Smith, “Donald Trump’s Star of David Hillary Clinton Meme Was Created by White Supremacists.” Mic, 3 July 2016.

- See Marshall McLuhan, W. Terrence Gordon, Elena Lamberti, and Dominique Scheffel-Dunand, The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man. Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 2011 (1st ed. 1962).

- Leonid Taycher, “Books of the world, stand up and be counted! All 129,864,880 of You.” 5 August 2010. For more historical data on books, see Max Roser, “Books.” Our World in Data, 2016.

- See Josh Constine, “Facebook now has 2 billion monthly users… and responsibility.” TechCrunch, 27 June 2017.

- This periodization is based on the date when Marc Andreesen’s Netscape Navigator, the first browser of choice for the World Wide Web, became freely available for download (Dec. 1994).

- Farhad Manjoo, “Social Media’s Globe-Shaking Power.” The New York Times, 16 Nov. 2016.

- John Herrman, “Online, Everything Is Alternative Media.” The New York Times, 10 Nov. 2016.

- See Shannon Greenwood, Andrew Perrin, and Maeve Duggan, “Social Media Update 2016.” Pew Research Center: Internet & Technology, 11 Nov. 2016.

- See Hunt Allcott and Matthew Gentzkow, “Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 31, no. 2, Spring 2017, pp. 211-36.

- See Sean Casey, “2016 Nielsen Social Media Report.” Nielson.com, 17 Jan. 2017. See also Jonah Engel Bromwich, “Generation X More Addicted to Social Media Than Millennials, Report Finds.” The New York Times, 27 Jan. 2017. The title in the print edition read, “Report Says Social Media Bewitches Older Users, Too.” The New York Times, 30 Jan. 2017, p. B2.

- Michael Nunez, “Former Facebook Workers: We Routinely Suppressed Conservative News.” Gizmodo, 9 May 2016.

- John Herrman and Mike Isaac, “Conservatives Accuse Facebook of Political Bias.” The New York Times, 9 May 2016.

- See Phillip David Brooker and Julie Barnett, “Where is the ‘alt-left’ on social media?” The Conversation, 13 Dec. 2016.

- See “Search FYI: An Update to Trending,” 26 Aug. 2016. See also Matt Weinberger, “Facebook reportedly fired a team involved in news stories – with an hour’s notice.” Business Insider, 26 Aug. 2016, and Dave Smith, “Facebook changed its trending news section last week, and it’s way less useful now.” Business Insider, 29 Aug. 2016.

- Zeynep Tufekci, “The Real Bias Built In at Facebook.” The New York Times, 19 May 2016.

- See Nick Wingfield, Mike Isaac, and Katie Benner, “Google and Facebook Take Aim at Fake News Sites.” The New York Times, 14 Nov. 2016.

- See Marty Swant, “Google Blocked Over a Billion ‘Bad Ads’ Last Year for Misleading Users.” AdWeek, 25 Jan. 2017. The categories under scrutiny include ads that promote illegal products, payday loans, click-to-trick (clickbait) ads, and “tabloid cloakers,” fake news that try to game the system for material and/or political profit.

- Alex Heath, “Facebook is giving media outlets more control over battling fake news.” Business Insider, 25 Jan. 2017.

- Alex Heath, “Facebook hired a former NBC anchor to help improve its relationships with the media.” Business Insider, 6 Jan. 2017.

- Quoted in Kate Conger, “Zuckerberg reveals plans to address misinformation on Facebook.” TechCrunch, 19 Nov. 2016.

- See above, note 15.

- See Matthias Lüfkens, “Twiplomacy Study 2017.” Twiplomacy, 31 May 2017.

- The ratio between real and fake followers, web robots, for example, is constantly changing and monitored by Twitteraudit. For a breakdown of Trump’s current ratio, see his “TwitterAudit Report.”

- Update Oct. 2020: Trump has now reached rank 7 with over 87 million followers. But he still trails Obama, who occupies rank 1 with over 123 million followers; see “Top 100 most followed Twitter accounts.” Social Blade, accessed 7 Oct. 2020.

- See Abby Ohlheiser, “Trump didn’t delete his tweet calling global warming a Chinese hoax.” The Washington Post, 27 Sept. 2016.

- See David Lazer, Oren Tsur, and Nicolas Rapp. “I. You. Great. Trump. A graphic analysis of Trump’s Twitter history, in five slides.” POLITICO Magazine, May/June 2016.

- For some funny Chinese examples, see Kassy Cho, “People in China Are Photoshopping And Sharing Fake Trump Tweets and They Are Outrageous.” BuzzFeed, 27 Jan. 2017.

- See Charlie Warzel and Lam Thuy Vo, “Here’s Where Donald Trump Gets His News.” BuzzFeed, 3 Dez. 2016.